Eugene Cernan: Purdue astronaut, NASA pioneer

Eugene Cernan became the most recent person to set foot upon the lunar surface during the Apollo 17 mission in December 1972. (Photo courtesy of NASA)

Read excerpts of Purdue students’ research from the Eugene A. Cernan Papers: Cernan’s Flight Expertise | Apollo 17’s Legacy | Common Ground in Space

Astronaut was a normal Purdue student who accomplished extraordinary things

One of Eugene Cernan’s greatest gifts was his ability to seem ordinary.

Of course, Cernan (BSEE ’56) was not ordinary. Far from it. There’s nothing typical about becoming one of 12 people – thus far – to have walked on the lunar surface, 50 years ago during the Apollo 17 mission. Nor is there anything common about Cernan’s experiences in space prior to the Apollo 17 voyage that made him the most recent human to set foot on the moon.

And yet Cernan had a way of making his otherworldly accomplishments seem accessible to the mere mortals who had never ventured beyond the Earth’s atmosphere. Whether interacting with presidents and politicians who determined the fate of the space program, Soviet cosmonauts who were fierce rivals in the race to space, celebrity well-wishers or members of the general public, Cernan possessed a unique ability to forge warm connections across societal or geopolitical boundaries.

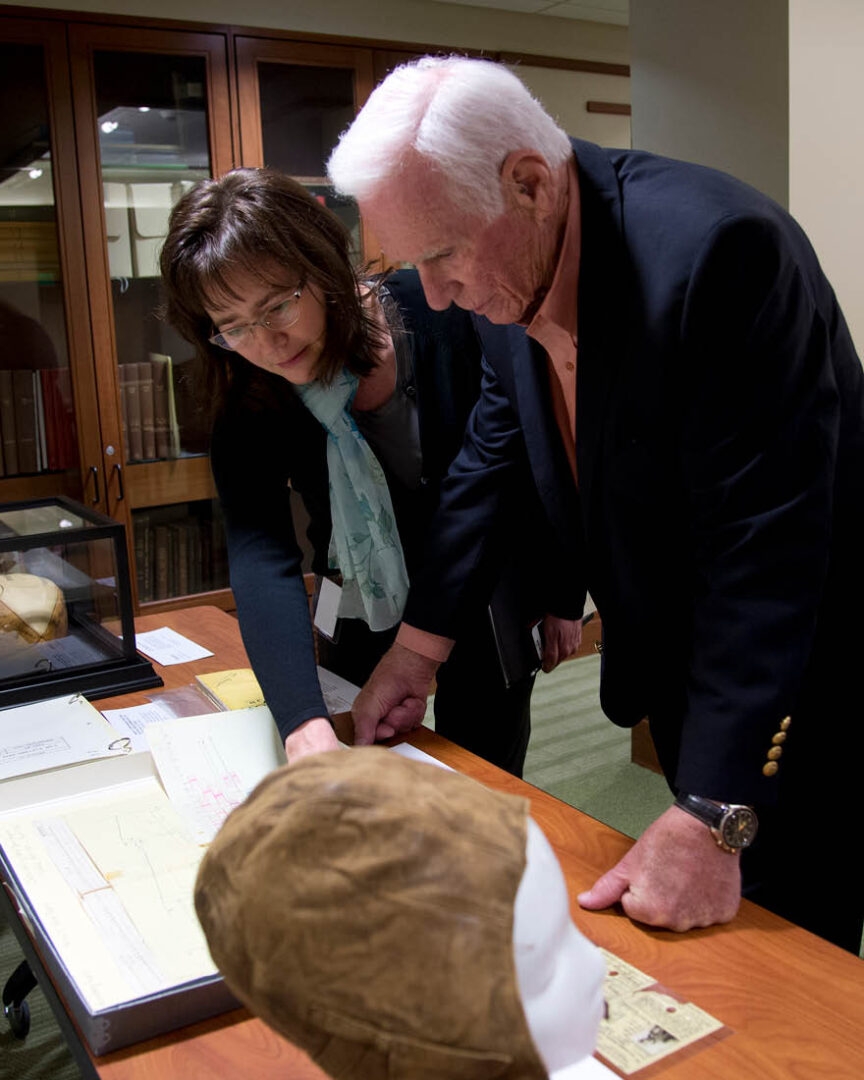

“He loved people. He loved life,” says Tracy Grimm, associate head of Purdue Archives and Special Collections and the Barron Hilton Archivist for Flight and Space Exploration. “I think that was just naturally his personality. I don’t think he was shy.”

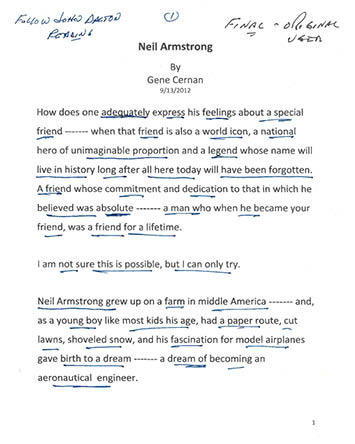

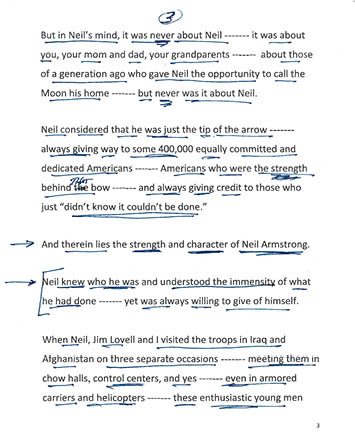

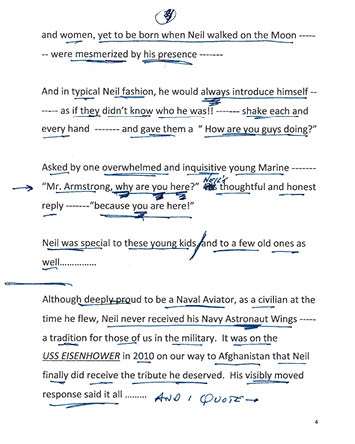

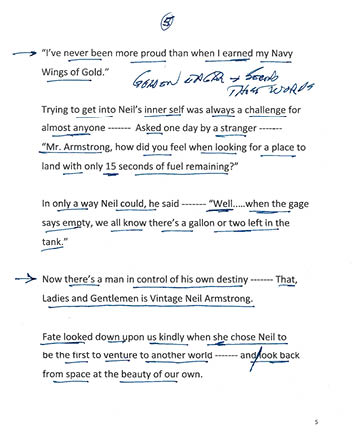

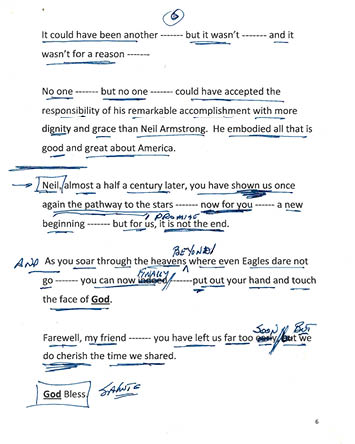

Grimm had reason to interact with Cernan on numerous occasions while facilitating his donation of some of the documents and personal effects now stored in Purdue’s archives, the Eugene A. Cernan Papers: 1934-2014. Among the highlights in the collection are resources the late Boilermaker astronaut gathered while preparing to write his autobiography, “The Last Man on the Moon,” with co-author Don Davis, as well as drafts of the book. He also donated a folder packed with notes and multiple revisions he’d made as he prepared to eulogize his friend and fellow Boilermaker Neil Armstrong in 2012 at the National Cathedral.

“In Eugene’s papers, he’s got handwritten notes for a lot of speeches he gave throughout the years,” Grimm says. “But for Neil’s eulogy, it’s a big, thick folder, and you can tell he spent a lot of time. He wrote, and then he wrote again, and then he wrote again, then he typed it up, then he typed it over. There’s a lot of versions, and he wanted to make sure that we had the final version where he underlined where he wanted to vocally emphasize and things like that. That’s something that gives you insight into him and what he cared about.”

Eugene Cernan Papers, Box 25, folder 18, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections

Utilizing Cernan’s papers

Grimm also helped Cernan share the story of the space program with Purdue students, including a class led by Michael G. Smith, professor of history in the College of Liberal Arts. In 2014, Smith introduced HIST 395, an archival research seminar where advanced undergraduate students utilized the Cernan Papers to learn how to conduct original historical research and writing. Their coursework included an introduction to the legendary astronaut himself, and Cernan lived up to his down-to-earth reputation.

“Cernan was personable,” Smith says. “He was joyful, kind, outgoing, smart and funny. When I first taught the seminar in 2014, my students met him at the archives, thanks to Tracy Grimm. He spoke with them and engaged with them at length, without any hint of pretension. He was genuine.”

Smith and Grimm co-instructed the Cernan research seminar again in Fall 2022 in recognition of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 17 mission, which launched on Dec. 7, 1972, and returned to Earth 12 days later.

The students learned about Cernan’s legacy as commander of the Apollo 17 mission, whose landmark scientific work still aids Purdue researchers today. They found that he was among NASA’s most experienced and capable astronauts because of his contributions to Gemini 9 – where he became the second U.S. astronaut to complete a dangerous, harrowing spacewalk – and Apollo 10 – where he piloted a lunar module to within 47,000 feet of the moon’s surface, setting up the American space program to successfully make its first lunar landing during Apollo 11.

They also learned that after his trips to space, Cernan served in a diplomatic role by helping to organize and direct the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the first crewed international space mission, where Americans and Soviets collaborated on a docking exercise and joint and separate scientific experiments.

It all started at Purdue, where Cernan was a typical college student who loved airplanes but had never even flown in one before his final year at the university.

“He was a normal Purdue student who went on to do extraordinary things,” Smith says.

Blue-collar roots

The Chicago native was initially hesitant to accept a partial Navy ROTC scholarship to Purdue over a full-ride offer to attend home-state Illinois, knowing that his working-class family would bear a substantial economic burden while paying his out-of-state tuition and expenses at Purdue. However, Cernan’s father insisted on Purdue, where he believed his son would receive an engineering education of the highest quality.

His path toward a degree in electrical engineering was no cakewalk, however. While academic success had previously been easy for Cernan, he struggled in the upper-level engineering courses. He later wrote that he had to “learn how to learn” in order to complete the more challenging coursework, knowing that failure was not an option with his family back home footing the bill.

He put in the work and succeeded, advancing from Purdue to the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School, where he received a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering in 1963. While in the Navy, he flew FJ-4 and A-4 Skyhawks as a member of Attack Squadrons 126 and 113 before getting the opportunity that would change his life. In October 1963, NASA selected Cernan as part of the third group of astronauts to join the Gemini and Apollo programs.

Even after the remarkable achievements that would follow, Cernan never forgot what led him to that point.

When he spoke at the 2007 dedication ceremony for Purdue’s Neil Armstrong Hall of Engineering, named in honor of his fellow moonwalker, Cernan addressed how that rigorous education paid off for himself and the other astronauts in attendance.

“I’ve been asked, ‘Why so many astronauts from Purdue? What do they do down there?’ I don’t know, maybe it’s because those of us who choose to come to Purdue come because we want to,” Cernan said. “I don’t know that we’re special, but I do know that when we leave here after the years we spend, we are indeed special. We’re Boilermakers. We come with one of the finest educations we can find from any university in the country. And whether we knew it or not – and probably most of us never did realize it – but the first steps any of us took into space were taken right here on this campus. There’s no question in my mind.”

I do know that when we leave here after the years we spend, we are indeed special. We’re Boilermakers.

Eugene Cernan BSEE ’56

Student research

This academic year was an ideal time for Smith and Grimm’s students to study the accomplishments of the first generation of space voyagers as a new generation prepares to return to the moon via the Artemis program. In upcoming missions, NASA plans to establish a long-term presence on the moon en route to the space program’s next massive accomplishment: sending astronauts to Mars.

“Apollo 17 was the end of an era of really aggressive exploration. It laid that foundation,” Grimm says. “There’s a foundation on the moon now that’s kind of sat there for a while, but it’s there. And now we’re picking up on it with the next mission, with Artemis and with a whole new generation of astronauts.”

In their research, the students took note of Cernan’s role as a link between the two eras among many other facets of his remarkable career. Here are excerpts from three of the papers the students produced, covering the expertise Cernan built as a space pioneer, the scientific accomplishments of the Apollo 17 mission at an uneasy time for the space program, and the common ground that Cernan found with his Soviet counterparts during their occasionally awkward interactions.

Excerpts from “Cernan’s Skill: Accumulating Flight Expertise in Gemini and Apollo”

By Alexandra Seneczko, junior in history

Ferdinand Magellan, Jacques Cartier and Sir Francis Drake.

These are the names of some of the most famous navigators in history, who braved the vast world oceans in the 16th century. They looked out at the horizon and were willing to push the boundaries of their understanding, where few had traveled before.

There is another frontier that humanity has dreamt of breaching for millennia. Space, like the ocean, is vast and unknown. Yet, it also requires great vessels and explorers to cross effectively and safely. Eugene Cernan was one of those explorers in the 20th century. Over three diverse missions for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), he proved that humans could master movement in the great beyond.

As a Purdue graduate in electrical engineering, and with a postgraduate degree in aeronautical engineering from the U.S. Navy, Cernan was an accomplished military aviator when NASA chose him for the astronaut corps. He was one among many accomplished and promising astronauts in training.

His first mission in Gemini 9 (1966) was not the most perfect by any means. Cernan and Commander Tom Stafford were able to conduct successful orbital changes. But other parts of the missions did not proceed smoothly. The crew was unable to rendezvous and dock with the Agena Target Vehicle. That effort failed because of technical obstacles.

Cernan’s Gemini spacewalk, only the second in U.S. history, was a near disaster. It was highly ambitious. NASA had been lulled into the belief that spacewalks would be simple and achievable. But Cernan had to operate in difficult conditions, fighting the immense pressurization as well as the overengineered suit, which he said had “all the flexibility of a rusty suit of armor.”

As Cernan remembered, “my exertions were taking a toll because what seemed simple during our Earth simulations was nearly impossible in true zero gravity.”

Yet for all his troubles, Cernan stayed for the complete duration of his spacewalk. He was unable to use an astronaut maneuvering unit, but he completed the other objectives: securing a micrometeorite impact package, changing the film in a camera and moving around the spacecraft.

Most of all, thanks to Cernan’s perseverance, NASA turned the mission failures into a learning opportunity on how to do better next time.

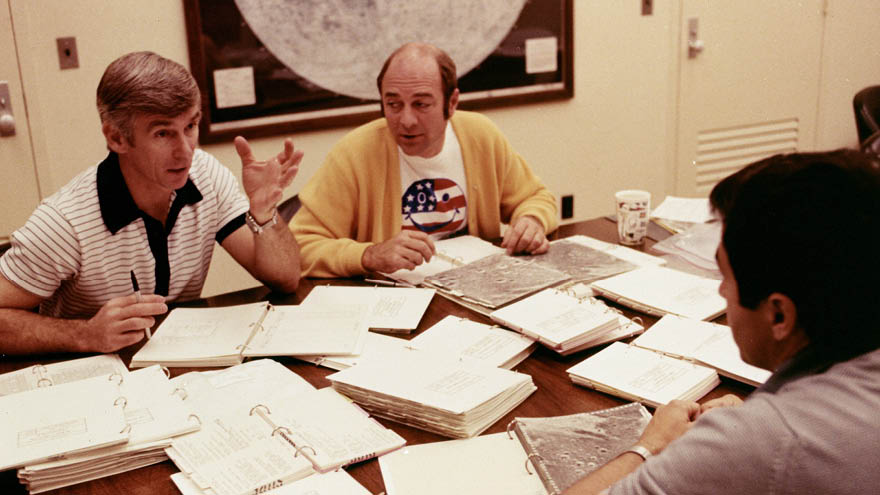

One of Cernan’s most triumphal missions was Apollo 10 (May 1969), a star-studded lineup when it came to the astronauts, all Gemini veterans.

Stafford was in the role of commander once again (he later flew on the Apollo-Soyuz mission). John Young was in the role of command module pilot (he later flew on two space shuttles). Cernan was the lunar module pilot.

He needed to navigate the module as close as he could to the moon without attempting a landing. This was the final step necessary to prepare for Apollo 11. As Cernan later reflected, “Apollo 10 would be a full dress rehearsal and do everything but touch down on the lunar surface.”

He and Stafford got very close: 40,000 feet above the lunar surface. Cernan was proud of their achievement: “Tom, John and I eagerly embraced our new roles as pathfinders. … We didn’t just know our machines, we had become an extension of them.”

In his last mission, this time as a commander, Cernan’s expert navigation of the moon during Apollo 17 (December 1972) made sure that the lunar lander and rover functioned successfully.

This time, Cernan not only landed on the surface, he walked and drove on it. According to the Apollo summary report, it was “the most productive and trouble-free lunar landing mission, [which] represented the culmination of continual advancements in hardware, procedures, and operations.”

Cernan and Jack Schmitt became ultimate explorers in their navigating about the lunar surface. Cernan ensured the operation of the rover, traveling around boulders and craters, over rocks and dust – lots of dust.

The moon was a strange landscape, but Cernan applied his engineering skills to move upon it: “You learned how to maneuver; you learned how to walk; you learned how to bend over to help each other. … You learned how to make your movements more efficient and productive.”

At one point, Cernan used his ingenuity to repair the bumper on the rover, fixing it with duct tape and parts of spare maps.

Through each of these missions, Cernan’s difficulties and discoveries, along with his accumulation of expertise in navigation, were foundational in NASA’s progress toward spaceflight and lunar science. He was arguably one of the most capable and experienced of all the astronauts of the Gemini and Apollo era: docking with target vehicles, conducting spacewalks, piloting lunar landers and driving lunar rovers.

One of his Italian admirers certainly thought so. Among his papers at the Purdue Archives, Cernan saved the letter and poem from Ignazio Giacchino of Milan, who praised the valiant crew of Apollo 10:

“You are the glorious instruments / of that celestial voyage / which gave you international fame. … To you, Stafford, Cernan and Young / fearless navigators traveling / the future Earth will celebrate your names.”

They were indeed pathfinders.

Excerpt from “Apollo 17: Between Political Mission and Scientific Expedition”

By Jacob Pranger, junior in history

On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong announced “one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” He forgot to mention one great victory for the USA.

There is no denying that the Apollo program was a product of the politics of its time. Apollo 11 was a mission with the foremost objective of beating the Soviets to the moon. NASA accomplished this.

Yet the question remains, why did we keep going back, seven times in all? The answer: for the science.

The Apollo program was paradoxical. It was politically charged, yet scientific. It was a flex of American muscle with scientific experiment as one of the end goals.

Apollo 17 has an unjust legacy as a disappointment, an unfortunate “the last one.” By December 1972, it was lucky to have even taken place.

The Nixon administration had cancelled Apollo 18 and 19, amid the high costs of the Vietnam War, economic troubles and public apathy toward the space program. Apollo 17 was only worth covering at halftime of the Monday Night Football game – then a relatively new and much more popular television event.

But we should remember that Apollo 17 was a unique mission. In terms of its lunar module crew, it partnered Commander Eugene Cernan and astronaut Jack Schmitt in the final expedition to the surface. Cernan had earlier piloted the lunar lander in Apollo 10, while Schmitt had a doctorate from Harvard – the first geologist to explore the moon. Cernan called him “Dr. Rock.”

In terms of its scope, Apollo 17 was a near-perfect completion of the whole program. It was the longest of the Apollo missions in spacewalks. This gave Cernan and Schmitt more time to traverse the lunar surface and perform experiments, about 75 hours in total.

Apollo 17 by far traveled the longest distance of all the Apollo lunar missions. Cernan and Schmitt made their way over 21 miles on the lunar rover.

Apollo 17 also brought back the most diverse and sophisticated number of lunar samples, over 240 pounds.

Science on Apollo 11 was an afterthought, just a few scientific experiments lost in the spectacle of a huge political and media event. Apollo 17 explored with detailed care the Taurus-Littrow, a huge basin filled with dark volcanic lavas.

Cernan and Schmitt never explored the whole area, given it was the size of a continent. But they did achieve an amazing series of scientific feats: new experiments of lunar ejecta and meteorites, lunar gravity and seismography, surface electrical and temperature properties, and subsurface studies by electromagnetic radiation.

Schmitt prefaced these feats with his very first words on the moon’s surface: the soil appears “like a vesicular, very light-colored porphyry of some kind; it’s about 10 or 15% vesicles.” Cernan was a bit less academic: “Gosh, it’s beautiful out here.”

Two very human sides of the Apollo program.

Cernan saw the moon not as a scientist, but as an explorer. He was transfixed by its otherworldly wonder, gorgeous with its craters and mountain ranges.

He remembered the dark beauty of viewing space from the moon. To Cernan, the sun and Earth were beacons of light in a void of black. Nothing compared.

As he said in one interview, “Our Earth is just too beautiful to have happened by accident. … I believe there has to be a creator … because I was privileged to sit on God’s front porch.”

The astronauts of Apollo 17 even took a famous photograph to match Cernan’s poignant words. It was the “Blue Marble” image of the whole Earth, a new symbol for the global ecological movement, soon posted on bumper stickers, flags and T-shirts celebrating the new Earth Day.

In his retirement years, Cernan advocated for a robust American investment in space exploration, be it a return to the moon or exploring Mars. He paid special tribute to his friend and fellow Boilermaker, Neil Armstrong, by recognizing his unique status as the “first man” on the moon. But he disparaged his own place in history as the “last man,” believing that he was only the first of many “last men on the moon.”

In a letter to Daniel Goldin, the NASA administrator, now stored at the Purdue Archives, Cernan said, “Too many years have passed for me to still be the last man to have left his footprints on the surface of the moon. I believe with all my heart … there is a young boy or girl … who will lift that dubious honor from me and someday take us back where we belong.”

As we return to the moon with the Artemis program and spacecraft Orion, it seems that he will get his wish after all.

In December 2022, Artemis retraced some of Cernan’s Apollo 17 steps, on its 50th anniversary, by taking its own successful orbit around the moon. It is only fitting that space travel pick up where Cernan and Apollo 17 left off.

As I take man’s last step from the surface, back home for some time to come – but we believe not too long into the future – I’d like to just [say] what I believe history will record: that America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the moon at Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17.

Eugene Cernan’s final words from the lunar surface during Apollo 17

Excerpts from “Common Ground in Space: A Study of Interpersonal Relationships Between Astronauts and Cosmonauts to Apollo-Soyuz”

By Alek Wisinski, junior in history

The period of the Cold War in the 1960s and 1970s amplified a divide between the capitalist West and the communist East. Yet behind the conflict stood brave celestial pioneers who sometimes held humanity above the conflicts of nations and ideologies.

Astronauts and cosmonauts alike found common ground in comradeship. They came to understand that they were a part of a larger mission, one that superseded NASA or the Russian Space Program.

Author Frank White has called this phenomenon the “overview effect,” the thoughts and emotions that spacegoers feel when they are subjected to celestial views and events. It is a “cognitive shift in awareness reported by some astronauts and cosmonauts, often while viewing the Earth in orbit.” It happens when they witness “firsthand the reality that the Earth is in space, a tiny, fragile ball of life, ‘hanging in the void,’ shielded and nourished by a paper-thin atmosphere.”

Despite their opposite belief systems and rivalries, this effect allowed explorers to discover a shared identity among the stars.

Cernan was a major proponent of the overview effect. He discussed it in every account of his missions to space, but his later Apollo 17 mission certainly provoked the feeling more than any other. Whilst on the moon, as Cernan wrote in his memoir, “the Earth kept drawing my gaze away from the bleak surface, and reality felt like a hallucination.”

Throughout the space race, astronauts and cosmonauts met and shared their experiences in a number of venues. In 1969, for example, just days before the Apollo 11 moon landing, Cernan met Maj. Gen. Georgii Beregovoi in Helsinki, Finland.

Cernan was born in Chicago and became an accomplished pilot in the U.S. Navy. Beregovoi was born in Ukraine and served as a fighter pilot in the Soviet Air Force in the Second World War. By the time of their meeting, Cernan had orbited the Earth in Gemini 9 and had orbited the moon in Apollo 10. Beregovoi had flown the Soyuz 3 mission in Earth orbit.

Cernan and Beregovoi first met at an official reception during an International Aeronautical Federation event in Helsinki. As Cernan wrote in a formal memorandum to NASA, now in his papers at the Purdue Archives, he found Beregovoi “most impressive.” Cernan had a “distinct feeling that he understood English very well although all of our verbal exchanges went through one of his two interpreters.”

They posed for a picture. Beregovoi had placed an Apollo 10 pin onto his breast pocket, but one of his Soviet handlers quickly told him to remove it. The politics of the Cold War and Soviet totalitarianism intervened to break the friendly moment.

Cernan took notice of the shift in Beregovoi’s demeanor and, in the last line of the memorandum, states that “I had the feeling he wanted to sit down and just talk about mutual experiences without the obvious restraint to which he was forced to adhere.”

Cosmonaut Beregovoi’s true feelings begin to surface when he and Cernan shared a private, one-on-one meeting. The two exchanged stories of their shared experiences in outer space. Beregovoi offered his tales of orbiting Earth for almost four days, and Cernan talked of his Apollo 10 mission. They shared images of their journeys and “they stimulated a great deal of mutual discussion.”

The meetings proved educational and enlightening for both men, a human moment that bridged the divisions of human conflict.

A pinnacle moment in the “overview effect” happened during the Apollo-Soyuz mission in 1975, when the U.S. and USSR joined their two spacecraft in the famous “handshake in space.”

Cernan was an official NASA adviser in the program and made many consulting trips to Moscow. There, he met cosmonaut Alexei Leonov. The two “got to know each other very, very well and had some good times together,” as Cernan reflected.

Their relationship was so meaningful from their shared experiences doing spacewalks: Leonov, the world’s first, and Cernan, the Americans’ second. As he remembered, “we used to talk about things privately that they would never talk about publicly.” Here was the “overview effect” in effect, in an astronaut-cosmonaut friendship.

Apollo-Soyuz was challenging. American and Soviet engineers spent considerable time integrating the Apollo and Soyuz systems. They needed to build a common docking module.

For the first time in history, Houston and Moscow shared research, tests and every sort of technical document needed for success. Fortunately, at this point in the space race, the two rival powers began to work together.

The mission was not a victory for any one country. It was a victory for both, a victory for humankind. “At docking, engineers in the Moscow control center stood up and applauded,” as Cernan remembered. At that same moment, “American controllers in Houston also cheered.”

The overview effect had been brought back home, to Earth, through the Apollo-Soyuz collaboration. It demonstrated that, despite divisions and conflicts, humans can come together to achieve success.